An Interview with Joanna Croston—Author of Mountaineering Women

We talk with the creator of the new book dedicated to female mountaineers

It wouldn’t be too controversial to say that mountaineering is often sold as a bit of a man’s world—but beyond the endless tales of bold men with fancy surnames, there’s a rich history of women pushing the boundaries of the sport.

Published by Thames and Hudson, Joanna Croston’s new book Mountaineering Women shines a light on some of these boundary-pushers—celebrating the accomplishments of 20 outdoorswomen from around the globe, from legendary Yosemite climber Lynn Hill to pioneering Nepalese mountaineer Pasang Lhamu Sherpa.

We caught up with Joanna to find out more about the book and why it was so important to tell these stories…

The book seems like such a big project—what was the seed that started it off? Was it something you’d been wanting to do for a while?

I work as the director of the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival—one of the world’s largest, and most prestigious mountain culture festivals. I’ve been here for 18 years—and over the years I’ve been hearing stories of women and their adventures and their achievements, but I noticed that there is kind of a hole when it comes to literature.

I first went to my publisher for another project that we were talking about, and they asked me what was the missing piece in the mountain literature realm. And I said that although there’s a handful of memoirs from women climbers, there’s no sort of comprehensive collection of women’s stories. So that’s where that seed came from. And I told them that I was waiting for someone to write this book—so they said to me, “I guess that means you need to do it.” So I did.

How did you start it off? What was the process of making this book?

Over the years—really just out of personal curiosity—I have been collecting names of women climbers that I wanted to learn more about. And so I had this 70-strong list going—and my first proposal to the publisher was to cover all these 70 women. But then we narrowed it down to 20—and it was very hard to decide whose story would make it in the book.

It was never meant to be a comprehensive history of women in climbing—it’d probably take someone ten years to write that—this was really meant to be a reactivation of some stories that I felt were maybe getting lost to the new generation.

So, for example, Catherine Destivelle is in my book. She was really quite famous in the 90s, but I was talking to some younger climbers here in Banff, who had never heard of her. That kind of made me think, “Oh, you know, some of these stories I think are really famous and celebrated and are not with some younger folks, and they’re actually brand new stories.”

So that was another reason to bring that to the forefront. Because I think as a woman adventurer myself, and I know this is true of many women still who are in the climbing world, there doesn’t feel like there’s lots of mentors. But in fact, there are—it was really just a matter of doing more digging to bring the stories forward. A lot of women in my book were quite modest and humble and were surprised that their stories might be interesting to others. So it’s kind of interesting—if you look at the tome of mountaineering literature, it is really chock full of amazing achievements by both genders, but the male stories are more prominent.

Museum.

The book goes right back to the early days of mountaineering in the 19th century. Can you tell me what the attitude to women in the mountains was back in that era?

The introduction to my book talks a lot about the 19th century. It was written by a woman named Nandini Purandare, who’s the president of the Himalayan Club, which is quite a prominent mountaineering club in India. She wrote about the first instances of alpinism, really. And they happened in Chamonix in the Alps, where mountaineering became—a sport, if you will.

The first woman to climb Mont Blanc, for example, really did it as a publicity thing. She really was not that interested in climbing—she went to the top of Mont Blanc really to make some money and find some fame, which I think she did. But then there were a few really, really committed female climbers in the 19th century who were really committed to climbing as a way of life.

And then the afterword of the book is by Ashima Shiraishi, who’s a very prominent Japanese-American boulderer. And she’s really speaking about what she believes the future of climbing is.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You mentioned how a lot of the women you talked to were quite subtle about their achievements in a way. They weren’t braggadocious about what they’d done. Why do you think that was the case?

I think historically men in this world of mountaineering have been encouraged to celebrate their stories and bring them forward. Once a woman had climbed either the Matterhorn or Mont Blanc, the response from the male climbing community was, “Well, now that’s what we would call an easy day for a lady.”

So then it kind of became this diminutive thing. And so I think that sort of attitude meant that a lot of these women were kind of flying under the radar because actually no one really wanted them to tell their stories because they’d diminished the accomplishments of men.

I think that changed much later. Lynn Hill is a great example of how that changed, because when she free-climbed the nose in Yosemite, she was the first person to do that, regardless of gender. She really showed the world that it had nothing to do with being male or female—she was just the most prolific climber of that moment. That was a bit of a game changer for sure.

What was the quote? “It goes, boys!”

Exactly. She really sort of set the bar. And a lot of these women did—but maybe it was a bit more subtle. Catherine Destivelle was hugely famous in France, and her climbs were all over the French media, but she’s maybe not as well known in North America.

And then there’s a woman in my book named Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner who is Austrian. She’s the first woman to climb all 8,000 meter peaks without supplementary oxygen. And again, she was very famous in Austria and in German speaking countries, but I feel like her story may have been lost recently with the younger generation, too.

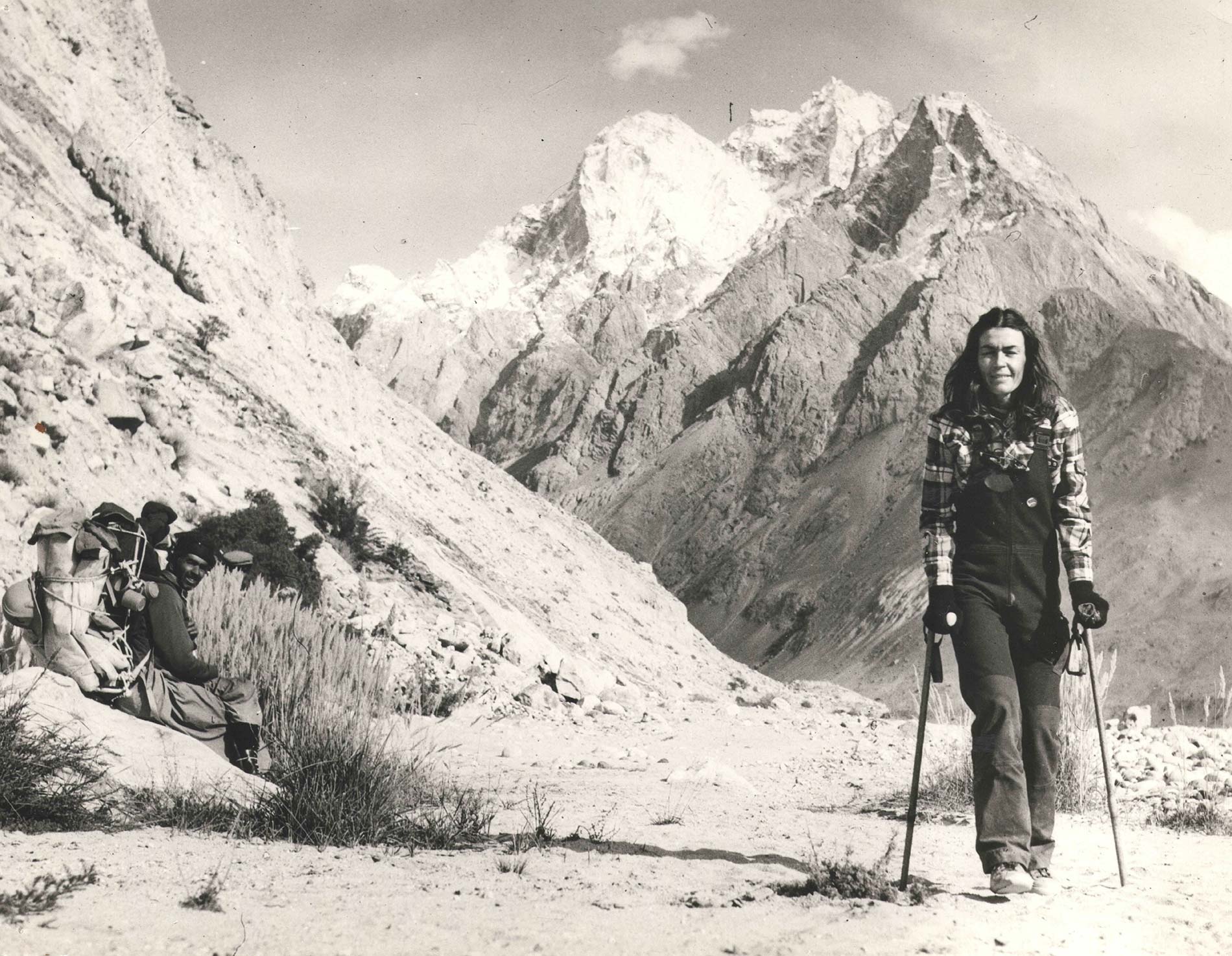

Archiv Kaltenbrunner.

In some cases, the agendas were quite different. Brette Harrington’s a great example of that, where she just really loves climbing and loves climbing for her own personal experience. Her climbs are really cutting edge, and don’t get me wrong, she has a really good social media following, but I feel like she’s a little toned down, compared to her male counterparts.

What is the lifestyle for these female mountaineers? And how has that changed? Are they able to make a living off these climbs—or do they fit them around another job?

I think this sort of phenomenon of sponsored climbing is actually not that old. Chris Bonington and a few people like that had this sort of presence and aura about them which meant they could organise these huge national expeditions and have the patronage of some very important people in the UK, but there was really just a handful of people, even male, who could make a living doing that until pretty recently.

When women first started being sponsored climbers, and I think probably Catherine Destivelle and Lynn Hill were among the first, they probably accounted for something like 1% of all climbing sponsorships.

Even Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner, when she was trying to do the 14 8,000 meter peaks, she was a full-time nurse. Her training would consist of her riding her bike at four in the morning to work every day—it was something like a two hour commute. And then she’d work all day and ride her bike home. And she did a lot of her first 8,000 meter peaks on her holidays.

A lot of the women in the book were working full time or they were mothers. Being a mother and a mountaineer has garnered quite a bit of criticism from the mainstream public. Alison Hargreaves was really criticised for leaving her family whenever she would go on these expeditions. And then, sadly, when she died, it was even more exacerbated where the media really hung on to this notion that she was an irresponsible mother for doing what she was doing.

And that’s never said of the male climbers. I don’t think I’ve ever heard that.

No one is calling the male climbers irresponsible fathers. I don’t know if you’ve read Beth Rodden’s book? She’s in the back of my book in a small section called More Mountaineering Women. She was also one of the first full-time female climbers, but her rate of pay she was getting from her sponsors was lower than her husband, Tommy Caldwell at the time. And of course, she knew that because they were married and she could see what he was making—and she was making much less. And she was climbing at a very, very high level—probably the best female at the time.

So even when there were these sponsorship agreements and they allowed women to just focus on the craft and climb full time, they didn’t have the same compensation. And I’m not sure that that’s even been rectified today. I think probably there’s still a bit of tokenism in some ways where brands will say, “Oh, we definitely need to have some women on our team.” but I don’t know about the pay equity part of it.

The box ticking thing—let’s get a few women in here so we don’t look backwards.

Yeah. It’s funny that even though women make up 50% of the population, it took a while for the brands to figure out that women would actually be great consumers of their product. They’re definitely there now though. And you see it a lot in the industry, especially in skiing, where there’s a lot of women’s specific equipment.

The North Face did a project with one of the sherpas who’s represented on their team, where she helped them design a full down suit for high altitude climbing for women. Because for years she had been wearing men’s suits which didn’t fit properly. I think for climbing, for example, there’s much women’s specific designs, but in the high altitude realm, it’s still pretty, pretty male dominated. It’s still pretty hard to get really small mountaineering boots, for example.

archive.

I don’t really know how to word this as a question—but are there kind of two routes here? There’s big brands and big ‘institutions’ trying to work out how to include women now, but then also, the women are starting their own brands or clubs or zines that sit outside of that. Is the future about working with the existing industry, or making a new one?

That’s a good question. I do think that some of the bigger brands are now sincerely diving into it and creating specialized equipment and clothing. But you’re right, I do think there is an opportunity there. Sasha DiGiulian is a great example, she’s an American rock climber, who started her own energy bar company, and I think the focus of that initially was women’s nutrition and women’s health.

So there’s these small little movements like that from specific women who are in the game at the moment—but I do feel like there could be more of that, and there is an opportunity there, and that is probably the direction things are going. But again, we’re still sort of caught in this consumerist mentality of what sells, right?

And there are still fewer women in the outdoors, for sure. I think historically they maybe have not been made to feel so welcome, and that still lingers, but statistics are actually getting more and more towards a gender equity scale than ever before. At some point, I’m sure they’re going to surpass that. I haven’t looked at indoor climbing statistics lately, but I suspect it’s pretty close in terms of who’s going—and I wouldn’t be surprised if one day there’s more women than men doing it.

There’s a lot of women-only training programs now. Sarah Hueniken, who’s in the book, runs ice climbing specific courses for women, and Hazel Findlay has very specific mental strength and training programs for women, too. They realise there’s a gap there. They wish they had this when they were coming to the forefront of their sports, so now they’re sharing that knowledge with others in the hopes that women will feel supported where they might not have been before.

I came to the mountains here in the Rockies in the late 90s. I did a lot of backcountry skiing—I still do—and back then I was often the only female in my group of adventurers. And I think my story isn’t a unique one with a lot of these women. I think that once they had a few male allies in these communities that really helped to accelerate their careers and for them to get respect. But it did take some allyship—it definitely makes it easier if you have a bunch of prominent male climbers supporting you.

Is one of the main differences today that we don’t rely so much on gatekeepers and institutions? With how the internet works, someone going out climbing with a phone can get a following and reach an audience, whereas 100 years ago they’d have relied on journals or clubs.

Yeah, absolutely. I think there’s a greater independence to women and how they’re conveying their own stories—the resources are available to them so they can tell their own stories.

You know, the Alpine Club in the UK didn’t allow female members initially. And so there was a group of really pioneering women who started their own ladies’ Alpine Club. They created this counter club so they could support each other and do the things they would do until the Alpine Club allowed women into it.

As you said, I think women having control of their own stories has been really critical. There’s still a little bit of a male dominance in terms of some of the brands and sponsorship deals and that sort of thing—but I think you can see it changing. Look at a brand like Rab for example, where their athlete and ambassador team is very, very well rounded.

Although you’d narrowed your list down a lot to make the book, it’s still got a really wide range of stories and voices. How important was it to feature stories that maybe aren’t as known in ‘the Western world’?

Yeah, it was really important for me to include those stories. For example, there are some very prominent Japanese climbers that Western cultures probably don’t know much about. Of course, I think everyone knows the Junko Tabei story—she was the first woman to summit Everest, so she’s probably a bit of an exception. There’s another woman in my book called Kei Taniguchi, who sadly is no longer with us, but she was a very prominent Japanese alpinist.

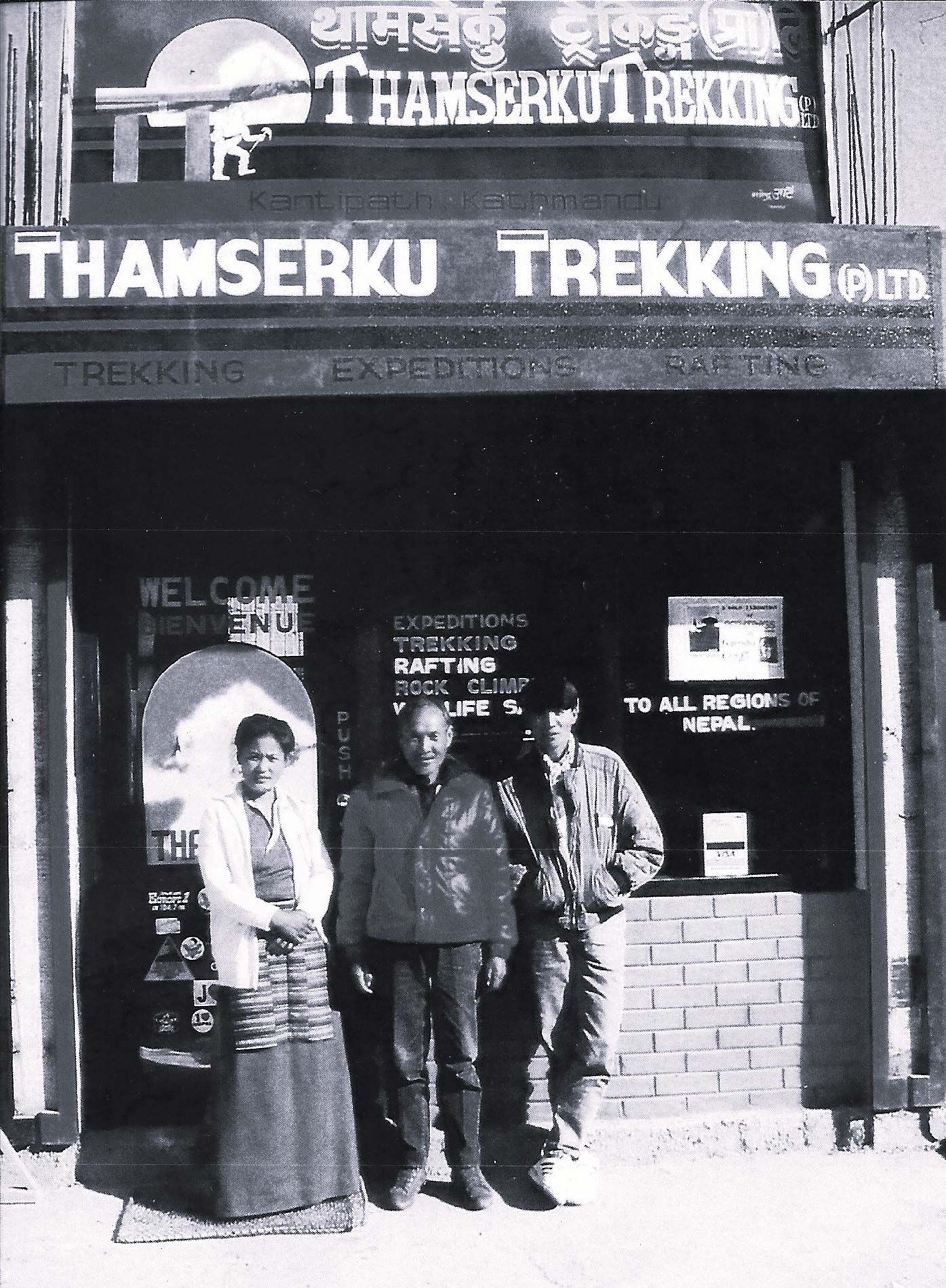

And then there’s the sherpani women—that’s really exploding at the moment—but there’s not loads of history on them. In my book I wrote about Pasang Lhamu Sherpa. She really was a pioneer in Nepal—she really thought it was crazy that the Nepali community—male and female—weren’t recognized by Westerners as climbers, and so she was determined to empower Nepali women. And that’s why she climbed Everest and did what she did.

And she met a lot of challenges and a lot of barriers in her approach. She had to go several times to the mountain and a lot of the time she was self-funded until she really got some recognition. And then unfortunately, with her death, she really became quite famous. There’s a monument to her in Kathmandu now.

I also wrote about Wasfia Nazreen. She’s the first Bangladeshi to do the seven summits and climb K2 and she summited Everest as well. And again, her purpose was to empower women in Bangladesh. She recognized the treatment of women is significantly different in her country than it would be in Europe, for example, and really felt a need to to bring attention to that.

So she was climbing with a purpose. With most of the climbs she did, she was climbing to show other women in Bangladesh that it was possible and that you could be an empowered woman in her country. And so her story is quite special.

I imagine that now the book is out, you’ll get countless emails saying, “I love the book. Have you heard about this person?” It opens up the conversation to find more of these stories.

Totally. It was always meant to be this sort of gateway piece of work that would just make people aware that the stories are out there and they really just need to find them themselves. And if you look hard enough, there is a lot to celebrate.

I’m really excited about the book and excited to present some of these stories to people for the first time if they haven’t heard them. I hope that’s what the book does—I hope it does spark an interest and encourage other women who are climbing right now to tell their stories in a way that will have some legacy.

archive.

This is a big question to end with, but how do you see women’s mountaineering evolving in the future? What would you like to see happen?

To be honest, I think the community that’s in place today is largely on track to really make things equitable. And I think you’ll see more and more mixed gender teams, really at the cutting edge of alpinism, for example. So I think the path is there and people just need to step onto it.

There’s some really great examples of women just leading the forefront. Ines Papert is a great example of that, where she really leads the charge in the ice climbing world—period. And Brette Harrington as well. There are some great examples for young women today, some really great mentors—they just need to take the challenge on. It just takes some grit and determination and things can happen. I think if someone’s got obstacles to overcome in their life—never mind in their hobby of climbing or family or work challenges—I think these stories teach you what the human spirit is capable of, and how deep you can dig if you really want to.

Mountaineering Women is available now. Find out more here.