An Interview with Aiguille Alpine Equipment founder, Adrian Moore

We talk with the man behind the Lake District backpack brand.

Since 1987 Aiguille Alpine Equipment have been making hard-wearing backpacks, built to stand up to the rigours of the great outdoors.

Whilst the outdoor industry has changed a bit since then, Aiguille have managed to stick firmly to their guns—ignoring gimmicks and trends in favour of their tried-and-tested designs, all made in their workshop in the Lake District.

Letting their bags do the talking, they’ve developed a strong cult following via word of mouth, making backpacks for everyone from the Mountain Rescue to Margaret Howell.

We talked with founder Adrian Moore to find out more…

This is maybe an obvious first question, but how did you get involved in making backpacks?

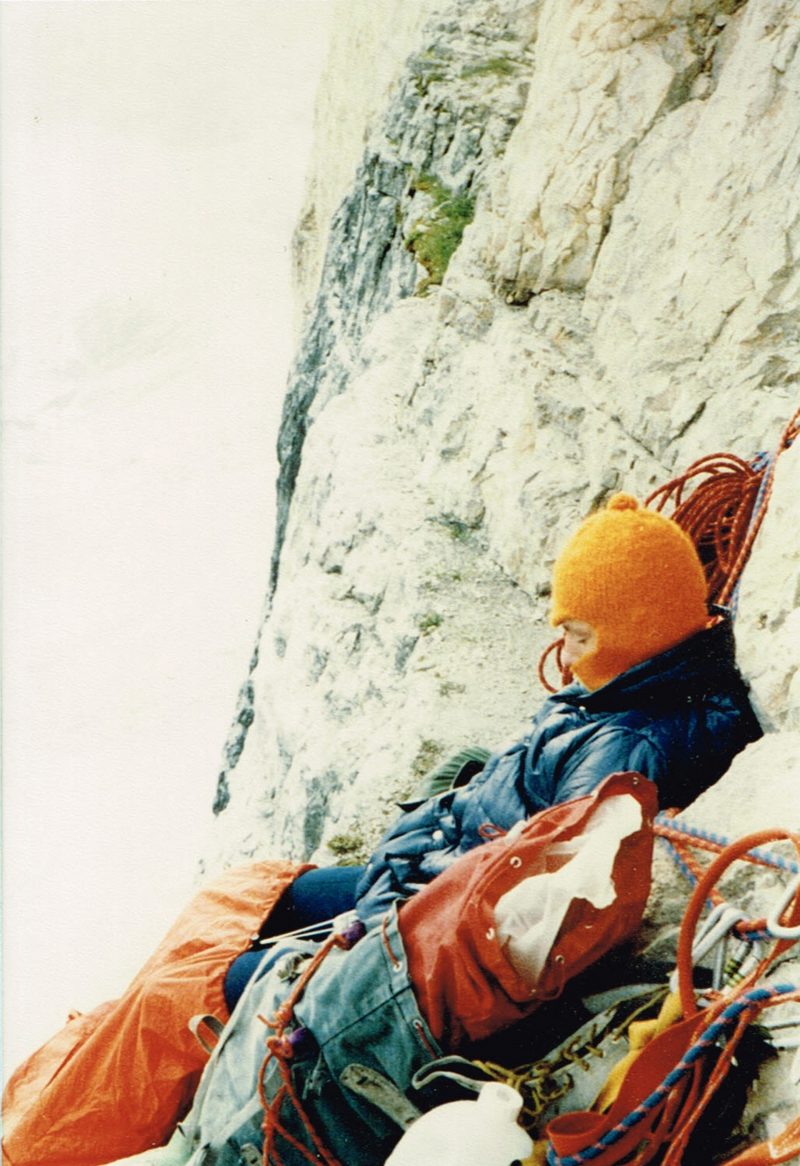

I started Aiguille in ’87, but I’d been making kit since I started climbing at the age of 12—which was in the early 70s. I was making gear for myself because I couldn’t afford it.

So it was something you were doing in your spare time anyway?

I was climbing all the time, I was trashing gear at a phenomenal rate of knots and I couldn’t afford to buy it… so I made it. I was sewing my own climbing slings on a domestic sewing machine. When I think of it now, I must have been off my rocker. I was making all sorts—rucksacks, etriers, jackets, everything.

Where do you think that mind-set came from? A lot of people just settle for what’s out there, rather than think to make something better themselves.

I’ve always had projects on the go—I suppose that’s just part of who I am. For my whole life I’ve been making things, or taking something that someone thinks is total rubbish, and rebuilding it. The amount of cars I rebuilt from scratch in my early years is untrue. I couldn’t afford the cars I wanted, so I’d rebuild them from utter wrecks—tuning Minis and Ford Escorts… I was just constantly making things.

What were you making your bags out of in the 70s?

Anything really. I remember making my first rucksack when I was 12 with the canvas from an old army kit bag. I had started climbing, but I didn’t have a rucksack, and I needed one. It was the same with jackets, they cost too much money, so I’d make them. And then I’d make etriers out of car seat belts which I got from a scrap yard. I was living in the Midlands, so it’s not like there were lots of opportunities for climbing around there—it was a slightly different mindset. I was just trying to get out to the hills.

Where would you go? The Midlands isn’t exactly famous for its mountains.

I started climbing in our back garden. We had two large oak trees, so I’d climb them. And then I turned the side of our house into a climbing wall. Because we lived at the bottom of a hill in a cul-de-sac, we had maybe 14 rows of bricks before the damp course on the side of our house, so I had a very large brick wall to play around with. I’d scrape a bit of mortar out and turn it into a climbing wall. I’d do circuits—climbing up the wall and onto an extension, then dropping down again.

“I remember making my first rucksack when I was 12 with the canvas from an old army kit bag.”

My father finally got fed up with me and dragged me off to a climbing club. But I couldn’t join as they would all meet in pubs, and I was too young. So whilst I was never an official member of a climbing club, I was a member of three or four around the Midlands unofficially.

How did all this lead into you making backpacks full time, with Aiguille?

My background is in design engineering. I got ragged off with that in the early 80s, just before it all imploded and a lot of the big companies folded. I did my apprenticeship in the Midlands, where there was a massive car industry—but then I basically gave up what was a very good job and moved up to the Lake District for a very poorly paid job in an outdoor centre. And then this sort of took over—it really started because I was trying to make money, and I could make things that people wanted to buy.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Did you already know there was a customer for your gear then?

I was making stuff for myself, but then someone said, “Can you make me one of them?” And that’s how it began. Aiguille has only ever been word of mouth. If you don’t count a website, we’ve never spent a penny on advertising.

Has it been a conscious decision to avoid all that stuff? As an outdoor gear company which has been going for over 30 years, it seems like you’ve managed to keep a good grasp of it still—and the product quality hasn’t dropped.

Yeah, I suppose that has been a conscious decision. I nearly went out of business when things started flooding in from the Far East. By the mid-90s, everything had gone off-shore just about, but we hadn’t. At the time I was supplying probably 20 or so of the key mountaineering shops around the country—and a lot of them were saying A – “Can you make rucksacks that last a little less time”, cos they wanted to sell another one, and B – “You need to advertise.” But at the time a full page colour advert in a climbing magazine was about £1,200 a month.

When I first started, because I’d come from an outdoor centre background, I knew Frank Davis—who owned the Climber’s Shop in Ambleside. If you discount all your Army & Navy stores, then this was, I believe, the first specialist climbing shop in Britain, in about 1959.

Frank said, “Come in and show me what you’re doing.” So I took a load of rucksacks in, and he said, “Yeah, great—if you’re still in business in two years, we’ll stock them. To take your rucksacks, I’ve got to drop someone else’s, and when you go bust, which you will, I’ve got to go back to them and try and get an account again.” He told me the figures, which were something like 95% of all businesses go bust within the first year, and of the remaining 5%, 90% go bust in the second year. He told me there was no way I was going to succeed. I said, “Oh great, thanks Frank!”

Not the most positive thing he could have told you.

So I just started giving friends of mine who worked in outdoor centres bags of kit to sell. They’d sell it on a commission basis—but I didn’t pay them in money, I’d pay them in backpacks. But the problem this created was that I was selling direct, which I suppose everyone is trying to do now, but at the time it meant that the shops didn’t want to stock the bags.

On the flip-side of that, we had always supplied outdoor centres—the actual centres and not just the people in them—from the word go. So we’d sell loads and loads into outdoor centres. We sell less to them now as most of them now just stay on-site as it’s cheaper, and they’re not doing expeditions in the hills any longer.

So we’ve always gone our own way. We had a full e-commerce website 18 years ago.

You were pretty early on that then.

Yeah, and that’s how it’s always gone. It just comes about from wondering, “How do we sell this stuff?”

You’ve made backpacks for the Mountain Rescue for years too. How did that come about?

Thinking about it, as we were (and still are) in the Lakes, we were approached by Langdale/Ambelside Mountain Rescue and they were probably the first people that we made medical rucksacks for.

At the time Mountain Equipment were making casualty bags for them, but had taken about eight months to make some. I ended up chatting to Pete at Mountain Equipment, and he was quite happy for me to take it off his hands. And we’ve been supplying teams ever since.

Looking at your bags, they’re a lot more straight-up then a lot of high-tech outdoor gear. Is that intentional? It’s an opposite way of thinking to a lot of the modern, lightweight stuff out there these days.

We make stuff that’s fit for purpose, and we don’t get het up with what looks, shall we say, ‘sexy,’ like a lot of other brands do. The bottom line is that we make product to go out there and be used. We’re not making rucksacks to look trendy. That’s not our market. We make climbing, walking and mountaineering rucksacks to use in that environment.

Is it hard to avoid the gimmicks involved in outdoor gear? The outdoor industry strikes me as being similar to things like cycling and fishing, where people are constantly being sold a new gadget.

To be honest, I don’t know, because we don’t particularly follow anything anyone makes anymore. I’m not really interested. We just do what we do. We’ll obviously listen to what the customers ask us for, but I’m not looking at what all the other brands are doing, and thinking we should do something similar to them.

“The bottom line is that we make product to go out there and be used.”

We are getting feedback from people who are current. My youngest son who works here, Chris, is climbing like I used to climb, and so are all his mates—and they’ll say what they want, as opposed to what I wanted in the 80s. Things have changed, but it’s still fundamentally the same. Some of our designs haven’t changed since we started making them, because a wheel is still round isn’t it? A rucksack is a potato sack with shoulder straps on—it’s for carrying a load, what else do you need to do with it?

You mentioned lightweight stuff… well, we think our rucksacks are pretty lightweight—but they’re not made out of lightweight fabrics. For example if you look at our Verte expedition rucksack. It weighs 2.13 kilograms—how much of that do you think the fabric is?

I don’t know. Maybe a third?

Well, you’re closer than a lot of people—it’s 22%. The rest of it is buckles and straps and things like that. It’s made of 1000 denier Cordura, which I think is pretty indestructible, and even if we halved the weight of the fabric, you’re only saving just over 10% of the overall weight.

And I suppose it’s much easier to repair something made of thicker fabric too.

The trouble with this lightweight stuff is that there’s nothing to sew onto. We constantly get people calling in here with a tear in a lightweight jacket, but there’s not much we can do with it. If you sew anything to it, it’ll be weaker. But this thicker stuff, it’ll take the abuse, and if you do get a hole in it, you can sew a patch on it.

Some of these new fabrics might sound sexy, but do they work? How long are they going to last you?

That’s what it boils down to.

We had a grandfather come in who still had one of our old rucksacks, and he wanted to buy one for his grandson. Isn’t that a returning customer?

Definitely. Even your supposed ‘lifestyle’ backpacks are just different colours of climbing rucksacks you already make. It’s not like you’ve skimmed off the quality for the ‘urban customer’.

The reason we ended up selling so many bags in London was because of the men’s lifestyle brand Albam. James, who started the brand, strolled into the shop one day and we got chatting. He said, “Would you be interested in making some bags for us.” At this point we were supplying loads of stuff into Japan anyway, and had been for a good ten or fifteen years. About four or five months later, he rang us up and said, “Look, this is the third meeting we’ve tried to set up, would you just make us a Midi Rucksack,” which is one of the bags we already make.

And we’ve worked with companies like Margaret Howell too. To be honest, when her daughter rang up to talk me, I didn’t have a clue who Margaret Howell was.

I suppose some people in your position would have thrown all the eggs into one basket and chased that market more. Was that something you were wary of?

It’s not even being wary—it’s not what we do. It’s not what we’re about. We’ll make the bags, but it’s not particularly what interests us.

How did the link with Japan come about? You make a lot of backpacks to send over there.

Again, that came from Pete Hutchinson who was by then running PHDesigins. He rang me up one day and told me he’d been approached by a Japanese company to make rucksacks. It wasn’t something they did, but he wondered if I wanted to do it. He said, “There’s the phone number, it’s up to you whether you ring it or not, but don’t blame me,” which was how things worked in the outdoor industry back then.

We followed it up, and we started to supply Japan, and we still do. And it’s great, but it’s fashion, so we can’t take it too seriously. It’s not what we’re about—we make rucksacks for climbing, mountaineering and walking.

We’ve got a portaledge to make for a company at the moment, and that order is far more interesting to us, it’s what we’re about.

Something like one of those Midi bags for example – how is something like that made? How long does it take to turn one of those out?

Now, there’s a good question. It depends on who is making it, and it depends what spec it’s at, but the record for making a centre-spec Midi, is about 30 minutes of actual sewing time. Admittedly that was just before Christmas when we were really pushed, trying to get people’s presents out for them.

Is that from fabric to something you can have on your back?

Yeah, that’s starting from having the cut panels in a box—but just the sewing and not the eyeleting, etc. Generally I’d say it takes about an hour and a half.

And they’re still made the same way you would have made a bag in the 80s?

Yeah—we’ve got better at making rucksacks, but the general process is pretty much the same.

A lot of company owners after a while end up distancing themselves from the thing that they originally set out to do, but it’s good the way you’re still very much involved in not just the making of the backpacks, but being outdoors.

I’m not climbing as hard as I used to, but I can still probably get up an E3 or E4 climb if I really want to. And I still do a lot of sailing when I can. Maybe not like I used to, but I’m a lot older than I used to be.

It sounds like you’re doing alright. I think I’ve run out of questions now. One last thing… seeing as you’re based in the Lake District, what should be people do in the Lakes to avoid the usual tourist zones? Have you got any good recommendations?

It depends what you’re doing. If you’re coming up to climb—get up onto the high mountain crags, and if you’re coming up to walk, do something other than just going up Helvellyn. Just don’t go where everyone else is going—there are loads of crags and hills to go at.

Find out more about Aiguille Alpine Equipment here. Workshop photos courtesy of Lisa Bennett.