An Interview with Rankin

Talking about AI and the future of image making with the legendary portrait photographer and magazine founder

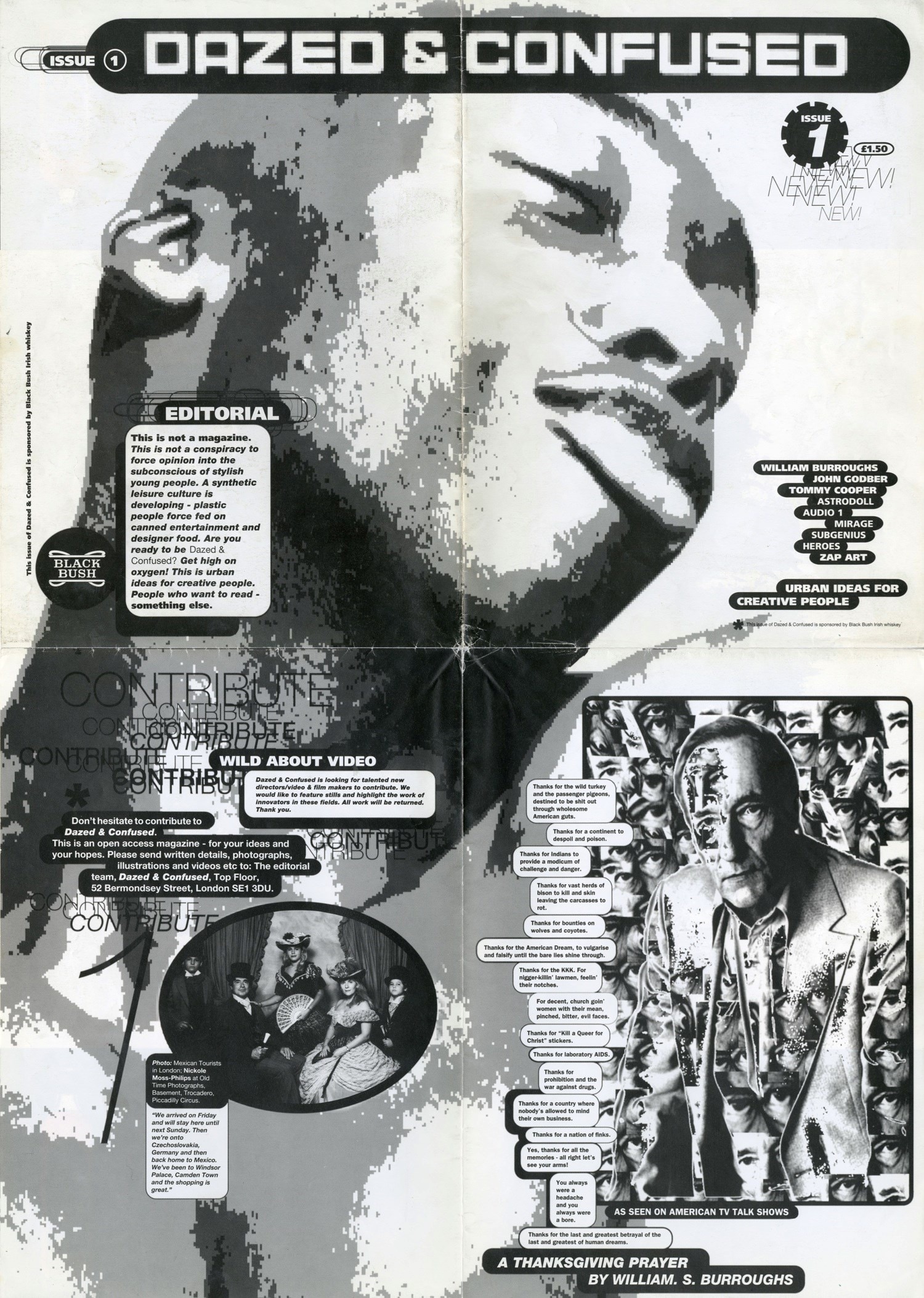

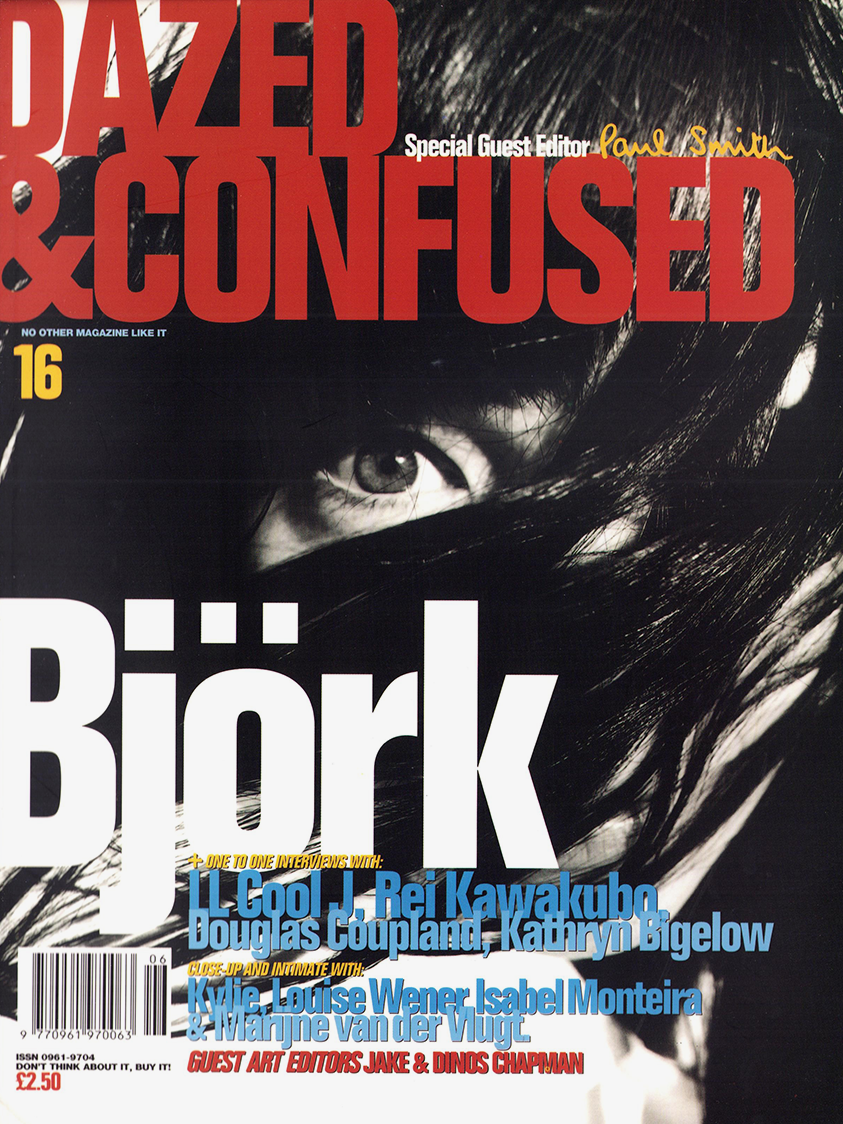

Those sci-fi paperbacks were right all along. The year is 2025, artificial intelligence has arrived and the boundary between reality and digital daydreams has been blown to bits. As most run for cover, retreating under the comfortable blanket of nostalgia, one humanoid seemingly not deterred by this confusing new age is Rankin—the photographer, director and Dazed & Confused co-founder whose fresh, high-gloss portraits of everyone from Kate Moss to David Bowie helped define the new millennium.

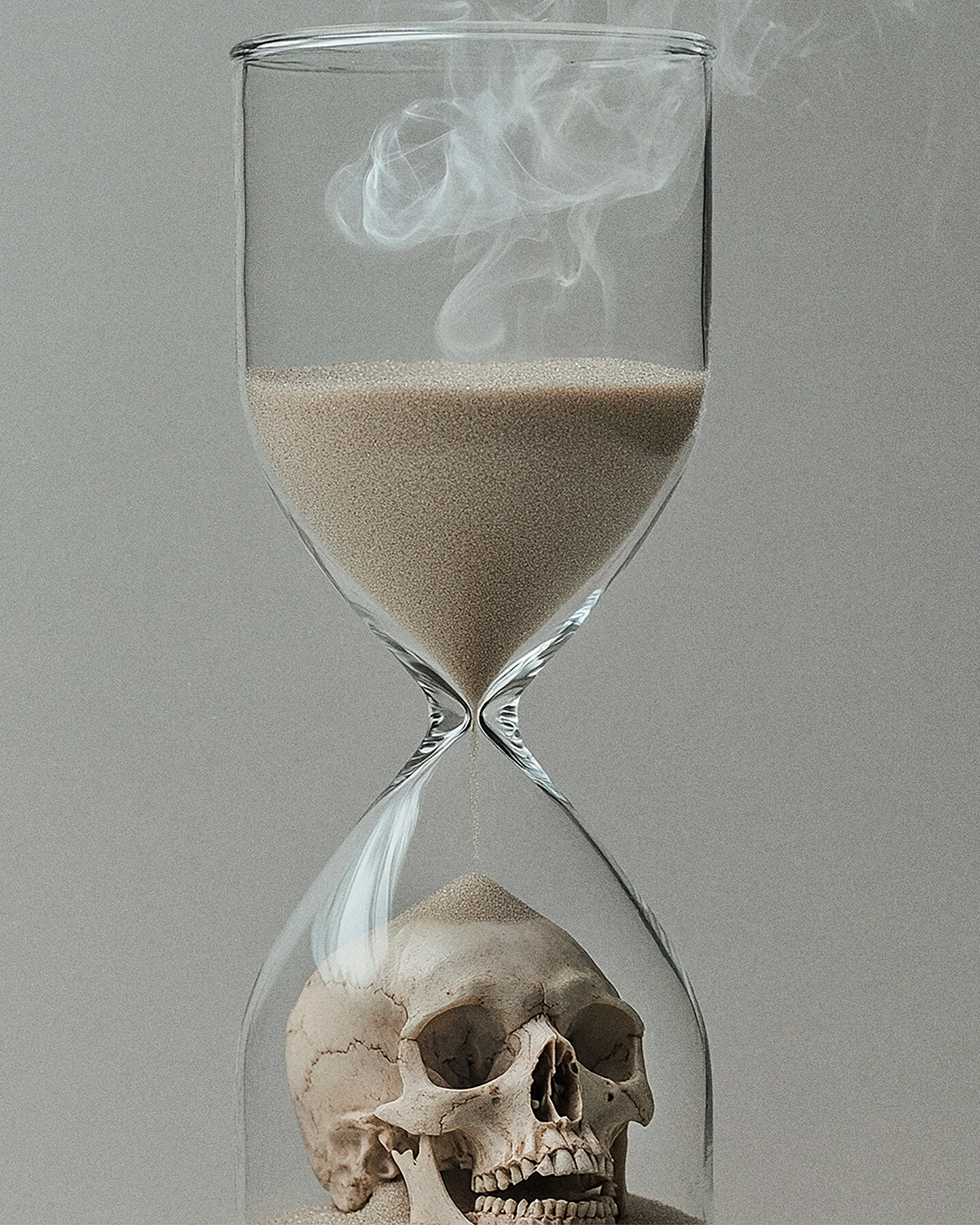

While you could maybe excuse an artist of Rankin’s caliber for just ‘sticking to the classics’, he’s done anything but—and over the last year he has thrown himself willingly into the synthetic abyss to create FAIK, a real-life exhibition and actual physical paper-based magazine which looks at this artificial intelligence malarkey head-on.

With AI still big on his mind, we plugged into the Matrix to chat with him about what it all means…

You’ve obviously been thinking a lot about AI at the moment—with both an exhibition and a magazine on the subject. What was the drive behind doing all that?

I think everybody that works in the fields that it affects will be inquisitive about it. If your business is being fundamentally attacked, you start to kind of think about it in a critical way. I’ve got friends that have been working with this stuff for years, and they’ve been saying, “Oh, it’s going to get to the point where it’ll be extraordinary.” And I just didn’t really believe them.

But you know—to be a photographer or any kind of creative, you have to be very inquisitive anyway, and with my upbringing, because I’m originally from Glasgow, I was brought up to ask questions and be a bit of a contrarian. That’s kind of in my DNA, so I’ve always genuinely asked lots of questions about things that I don’t really understand.

My initial thoughts and ideas were just like, “Well, I don’t want to be that person that judges it without actually having tried it.” I can’t be someone slagging this stuff off—I wanted to be informed about it, so I got some advice on how to use it, and from there it just built out into this inquisition.

I started to do some projects, and I was getting really good results very quickly, which was quite surprising to me. I started to do things, and then those things became little kind of games with myself, and then after three or four months, I thought I’d make it a more considered piece, and I then kind of built out an idea to do a magazine—looking at this new media through the analog lens of printing and making a making a magazine.

Subscribe to our newsletter

After all this work, how do you feel about AI now?

It took about a year in total to do it, and I can only describe it as being similar to one other thing I’ve done—which was a project I did about death. Doing that I went through these really weird feelings and emotional ups and downs about how I felt about death—and it was similar with this. It was like going through mourning, with anger, frustration, depression, and then finally coming to terms with it, but still being kind of scared of it. I’m not scared of death, but I’m definitely scared of this.

You fully threw yourself into this. Those feelings are kind of natural when you fully go beyond your comfort zone.

Yeah, I’ve gone in. I’m deep in it—I’m up to my eyes in it. It’s extraordinary to do, and the thing that I’ve realised was I have always had two parts to my work—there’s that creative, art director, creative director, ideas thing, trying to create photographs of my ideas—and then there’s my passion for portraiture—dealing with people one-on-one. And this AI thing takes that first part—that creative part—and unleashes every potential thing you can do in the world.

“Morally you feel bankrupt, but if you don’t use it, you probably go bankrupt.”

So it’s the most incredible gift—I’m like a pig in shit—enjoying being able to do anything I want, and at the same time, it’s a kind of event horizon moment for photography. And I love photography—it’s probably the love of my life—I love my family and my dogs, but the photography thing keeps me sane, so this is like these two things smashing together. I’m absolutely in love with this thing, and I actually hate it at the same time, and then on top of that, to make matters more difficult, I’m essentially having to use it, because I need to compete. I’m so conflicted in the whole thing and morally it makes you feel bankrupt, but you know what? Morally you feel bankrupt, but if you don’t use it, you probably go bankrupt.

Looking at it the other way, does this machine which churns out artificial images in seconds make real photography more valuable?

Of course, I think everything that’s real will become more valuable 1000%—but I don’t think the people that value authenticity are necessarily the people that make decisions about the masses.

Just so I get it clear in my head—when you’ve been using it have you been making images completely from scratch? Or have you been starting off with real photos and then adapting them with AI?

Yeah—I’ve based a lot of the images on ideas I’ve had in the past—they’re either things I’ve shot, or things I’ve tried to shoot before. I used to do a lot of stuff with filters when they first came out—so I recently regenerated them as sculptures. It’s an extension of what I’ve been doing with photogrammetry and bronzes anyway, but what cost me 20 grand to make years ago cost me five minutes to make online on a system.

Often it’s seen as humanity versus machines, but from what you were saying about how you’ve been using it, there’s a human behind what you’ve been doing. The magazine didn’t just emerge out of thin air.

Yes, the human plus machine is always going to be better than the machine—but to take a sky high view of this thing, it’s only going to get cleverer and cleverer to the point where it starts thinking for itself and deciding not to do what the human says. I always think of that movie War Games. How do you get to that? And if it gets to that how do you outsmart it?

It’s already miles and miles beyond just copying people’s photos. I think we’re kind of beyond that as a discussion—the horse has already bolted on that one. I feel like the work I’ve made with it is mine, but when people have been asking if they can buy the images, that feels so weird to me. I’m in such conflict about it—you’ve kind of got to laugh—you’ve got to go, “Yeah, you’ve literally unleashed the dogs of Satan on the world.” Let’s see what happens, let’s roll that dice.

For a bit of context I suppose, when you started being a professional photographer and making magazines in the early 90s, what was the process then compared to now? What were the kind of conversations going on then about what was fresh and new?

Well, we in a way bust the doors down on independent publishing. By the 90s there were only a few independents out there and we were very influenced by Andy Warhol’s Interview and by what the guys at The Face and iD were doing and what they did with Oz or Nova in the 60s—and desktop publishing technology allowed us to smash it down and go for it.

On the first day I went to college, I got the college magazine and I immediately became part of the student union that made that magazine, because I could suddenly see that I could make a magazine—that was a revelation. In a way I studied photography, but I studied magazine publishing in parallel and that allowed me to become a publisher. I always treated the magazine like a kind of art piece—like a Trojan horse that can go out into the world as this thing that you can hold and read, that has art in it.

In a way we started a bit of a revolution with a few other magazines in terms of representation, identity, identity politics, conceptual fashion, conceptual photography or art photography mixing with commercial photography. We wanted to put meaning and creative substance into a medium which had become mass produced and was almost pervasive in its kind of emptiness. We tried to put some art into that.

And everything I’ve done since then has been influenced by the fact that we were successful in making something that was a challenger in that period, and I don’t think I’ve ever really swayed away from that really. FAIK has a direct thread back to what I was doing back at that time.

“We wanted to put meaning and creative substance into a medium which had become mass produced and was almost pervasive in its kind of emptiness.”

Back then I couldn’t afford to build a set—but now you don’t have to. There was such a glass ceiling around the financial side of photography—even becoming a photographer cost a lot of money back then. I had to work three jobs when I was studying, just to earn enough money to pay for film and processing and all that stuff. And I think that’s gone—and that’s great. There’s been this democratisation of image making now—the playing field is very flat now and everybody’s starting off at the same point.

That means that you’re going to see work by extraordinary people whose minds might not have been able to explore this stuff, and I think that that’s what we tried to challenge back when we were starting. We might not have been rich, but we were coming at it like we were. We were culturally rich or confidence rich—and there’s no barrier to that anymore.

It’s suppose it’s like with music producers and how you don’t need a studio anymore. 20 years from now, what’s going on with photography? Does it still exist, or by that point are people just conjuring?

I think it does—I think there will be real photography and there will be real photographers who make pictures and the fact there’s a camera in everyone’s pocket means that people are still going to keep taking pictures. And real photography by masters of the craft will exist because I think that type of stuff lives out in any media or medium. I think, as you said, that it will be seen as having value that’s beyond what any of this stuff can do—but I think there will also be a place for this other thing. I think that authenticity will be valued very highly but I also think that it will be a rocky road for the next at least ten years before it balances itself out.

And I’m kind of up for the fight—I’m not shirking away from this stuff. I’m a photographer, I take pictures every day, I love taking pictures and I’m not scared of this AI stuff, I’m in it, I’m bending it to my will with a really vast knowledge of photography. I’ve got this curatorial ability to make work that’s much more realistic and has a theme and has consistency—I’m not doing fantasy, I think the fantasy element to it is a little bit ridiculous.

Yeah—the stuff I’ve seen is very much down the fantasy angle.

It’s also got loads of inbuilt biases.

Definitely. It always has the same look to it with that weird hyper-real sheen. But I imagine in a few months’ time it’ll be wound down a notch so it’s not so obvious.

You can say to it that you want to create a series of images like Diane Arbus—you can ask for it to give me 15 prompts to create a series. And maybe you want those images to be based on Hackney right now—to feature real people from Hackney. And it will create a series of Diane Arbus’s pictures shot in Hackney, and it can modernise them to make them feel like they look like they’re shot now. But I wouldn’t go to Midjourney and ask it that—I would go to ChatGPT, ask it to do the prompts, and then I’d go from the prompts to Midjourney to create it, or I’d go to Sora and create it immediately, and then I’d go from Sora to Midjourney to recreate it…

But does it kind of suck though? I know it can create the final image—but those Diane Arbus photos were good because they actually happened. She was a real person who went out everyday and took those photos. There’s a story there.

Yeah, of course.

I always think about Fitzcarraldo. That’s a crazy film—and they really did that—they really got that boat over that hill. If it was just made on computers, film students wouldn’t be sitting talking about it three in the morning. The real story is what makes it good.

And I think that that’s another thing that I haven’t actually said to you—one of the other things that I’ve been doing when I’ve been creating these sculptures is that I’ve been trying to write about why I’ve made them, as opposed to just pressing the button. Why did I make these? Why have I made these parodies on filters and death and, you know, all these themes that have been running through my work for 30 years? But my point is not that, my point is that most people won’t care.

So, yeah, and it’s like, do they just want the end bit—the final product?

Yeah—a mate of mine sent me a film that was all done with AI, but it had this really weird meaning to it. It was almost an art film, but made with AI, and it gave it credibility and credence. It goes back to art—what’s the best art for you as a creative—I think that’s something that makes you feel and think something. Now if anything can do that, then it’ll have the power.

If you ask me why I take photographs, it’s because they’re a capsule of something that goes out into the world, and they touch other people, and make them see the world the way that I’ve seen it, and I’ve understood it. And you can still do that with an AI image. I think people will kind of reverse into it.

It’s already happening in a really naff way—like where people might make a ‘making of’ film of an AI film—and it looks like it’s a real ‘making of’. At the moment people are saying, “look at what I did with AI—look at how good I am at this,” because they’re trying to get work out of it. But very soon it’ll tip over and they’ll stop telling you that it’s AI.

I suppose soon we’ll be beyond the conversation, and it’ll just be like, “This is just work”, in the same way someone used Photoshop, or someone used a digital camera, they don’t have to tell everyone first. That thing of whether it was AI or not will be kind of irrelevant.

There was a study done recently—they showed 109 images of human beings to 150 people and told them that around half of them were AI, and then asked them to work out which ones were real, and which ones weren’t. Around 44% of the photos were judged to be AI—but they were all real! So, the minute you use the word AI, people are already looking for it.

You’re looking for the strings on the puppet.

Exactly. In the back of the magazine I said, “Imagine if I just made this and hadn’t told anyone?” You would all have thought it was real, because I’m an accomplished photographer who could probably have made all of these images, or at least 80 percent of them. And that’s the thing that no one’s really talking about. When we stop admitting that this stuff is AI, then we’re suddenly into a world of crazy truth.

It’s like the Cottingley Fairies, isn’t it?

It’s the Cottingley Fairies all over again. So, to me, it’s like, that’s the bottom line of all of this stuff, and we’re right at the beginning. We’re like infants, pre-primary school. This stuff hasn’t even kicked in properly, really, and we’re still debating the wrong things. We’re debating that the guy’s got three fingers, but look at all the rest of it. It’s so realistic.

Anyway, I could go on about it all day, but it’s just a minefield, and I’m quite enjoying it. I’m hoping I’m not going to hit one. I’m hoping that there’s going to be an optimistic end to it…

FAIK is running until the 26th of June at Annroy Gallery. Find out more here.